Dr June Oscar AO will chair a new institute at the Australian National University that will advance the voices of First Nations women and girls.

The Wiyi Yani U Thangani First Nations Gender Justice Institute was launched this week, and will continue the work of the Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women’s Voices) Project that Oscar has led for the past seven years at the Australian Human Rights Commission. The institute will be supported by $3 million of government funding over four years.

It comes as Oscar’s term as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner nears its end.

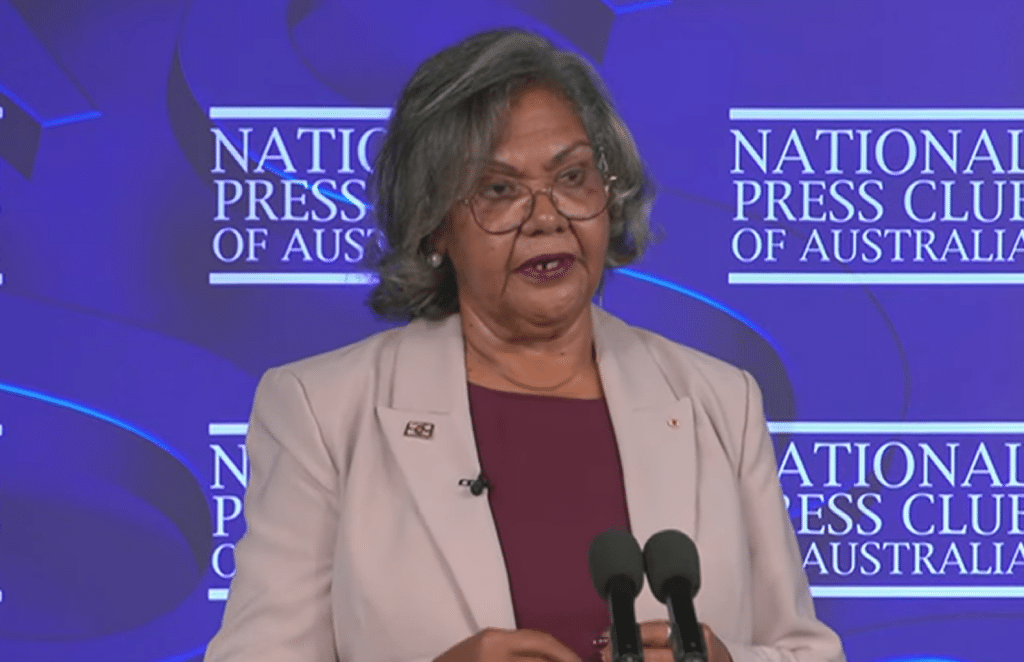

“I know that our women and girls live rich lives, which matter to the healthy formation and growth of societies and environments. But we’ve been made invisible by a narrow frame of deficit,” Oscar told the National Press Club on Wednesday.

“Through the Institute and change agenda, we’ve put on the national landscape a visionary framework that defines our rights and shows in our entirety all the work we bring to the world. We have a new frame to see a First Nations gender justice lens.”

In her speech, Oscar spoke about her great-grandmother who lived through the killing times of the Bunuba people in the Kimberley in the 1890s. By the 1930s, the Bunuba people had been reduced to a tenth of their size before invasion.

“In the greatness of our civilization, spanning millennia, this was apocalyptic,” Oscar said.

“My grandmother, living in the aftermath of this decimation, turned her back on white society. Like others who have survived, she used all the knowledge passed to her and refused to send my mother to school, saying to her, ‘I will teach you everything you need to know’. In turn, they both did the same for me.”

Oscar explained that “seemingly ordinary everyday acts” by the matriarchs in her life were “powerful forms of resistance against a colonial system that had attempted our eradication”.

“A system that insisted this new Australia was not for us and denigrated our women, implicitly condoning gendered violence, abuse and rape,” she said.

“Long before any feminist or gender equality movement, my matriarchs and the men in our lives knew the vital place of our First Nations women in constructing healthy ecosystems and conditions of balance, wellness, and safety for everyone.”

The value of care work

Oscar spoke about the importance of building a stronger social fabric and valuing the care work that First Nations women do.

“Rather than weaving together the social fabric, we are pulling all our reserves into safety nets, constantly responding to the crisis born from trauma and hopelessness,” she said. “Those wicked problems of widespread addictions, suicides, family violence, poverty, and cycles of incarceration”

“Recent research we’ve released with partners at the ANU and the Queensland University further outlines the burden of care women have and a total lack of recognition that our care work is keeping our societies together.

“It estimates that the market value of our work in annual salaries is between $81,175 to $118,921 per First Nations woman. This is the devaluing of the work that creates the social fabric.”

On the Voice referendum

On the failed Voice referendum, Oscar said “whatever you thought of it”, it was a “mirror moment” for the nation.

“I still believe it can be a vital wake up call, with the potential to bring all Australians into a process of reckoning with the idea of Australia and how we want this nation state to embody the values of a diverse Indigenous and non Indigenous population.

“We have an incredible multicultural tapestry… Australian families are from across the globe. We need to go on a journey to truly honour that.

“Referendums placed us in a binary but if we look beneath the binary, as the lens of gender justice insists, we will find a much more complex story.”

Oscar said the Voice fell victim to what it aimed to counteract, that is, mass discontent with socioeconomic conditions which have given rise to sectarianism and populism.

“This burgeoning industry of lies and discrimination, masquerading as truth and justice, erodes our trust toward each other, government institutions, and for me, most significantly, our ability to work together,” she said.

“We are vulnerable to turning away from one another to fear and anger. This is the direct opposite to what my grandmother taught me… that we must all be givers of care and nourishment to each other and the country.”

On the age of criminal responsibility

Asked about the age of criminal responsibility, which remains at 10 in some jurisdictions, Oscar said she doesn’t believe in locking up children.

“I think that act speaks to our incompetence, our inability to respond in a far more therapeutic, healing and rights-based way,” she said. “And so, when we look at the criminal age of responsibility – and yes, the cases for whether it should be 10 years of age, 14. I just think – children are children.

“We should be treating children based on their rights, based on the need for guidance, for support, for love, as we’ve heard in the messaging from the grandmothers who are calling for the closure of Don Dale. From the women who stand outside of those detention centres and argue based on humanity and fair treatment of children. I think that’s a key point that we need to revisit.”