In Australia, more than one in four girls suffer childhood abuse.

That’s according to the Australian Child Maltreatment Study (2023-2025) which also found its lasting effects include depression, substance use, homelessness, unemployment, eating disorders, suicidal ideation and self-harm.

These are grim statistics.

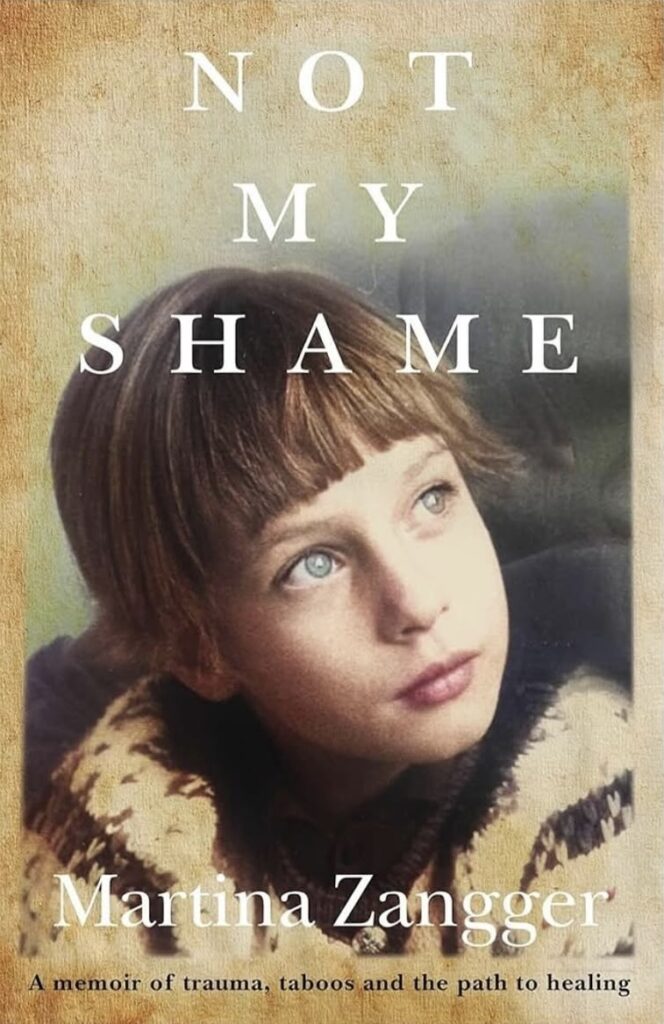

I am a victim-survivor of early sexual abuse by my grandfather, a Swiss high court judge and by my uncle, a well-loved Swiss politician.

As a result of years of sexual harm, and to my strict, middle-class parents’ horror, I made numerous cataclysmic decisions in young adulthood. Despite HSC results in the highest percentile, I dropped out of university six weeks into my first semester. Aged nineteen, I joined the cult of the notorious Indian guru Rajneesh and became a sex worker to save up the large sum of money I needed to live with the guru, the owner of eighty-four Rolls Royce. You may have seen the Netflix series Wild Wild Country documenting the cult of the infamous guru.

Soon, I found myself juggling three names and identities, each representing a different facet of my being. Martina, the name my parents gave me and which I had rejected; Pragito, the one my guru bestowed on me; and Zoe, the alluring alias I embodied at the upmarket Sydney brothel where I worked.

At twenty-seven, I finally found the courage to disclose my childhood sexual abuse to a trusted friend. Soon after, I was able to break up with the guru and eventually found healing in the sanctity of the therapy room. Over time, I discovered the empowerment of tertiary education. I worked at the coalface in rural and regional sexual assault services and later as a psychotherapist with victim-survivors in private practice. I became a university lecturer and completed a PhD on sexual assault and the legal system.

I reclaimed my life after breaking the trauma bond.

With Blue Knot Day fast approaching – a national awareness day that calls for the support of survivors of childhood trauma and abuse, it would be remiss of me not to speak out.

I no longer believe that the sexual violence I endured was my fault and I firmly place the blame where it belongs. My hope is that there is systemic change which sees the shame shift from the victim and be placed fairly and squarely on the perpetrator.

Research findings state that less than 13 percent of women report sexual abuse to police, and fewer than 10 percent of sexual assaults reported lead to a conviction (Bureau of Crime Statistics, 2024).

A study by the University of NSW found that in Australia, one in six men admit to being sexually attracted to children under the age of 14, and one in 10 admit they have sexually abused a child. These men are ordinary men, as my own abusers were. The famous psychiatrist Judith Herman aptly writes:

‘His most consistent feature is his apparent normality. How much more comforting it would be if the perpetrator were easily recognisable, obviously deviant and disturbed. His demeanor provides an excellent camouflage, for few people believe that extraordinary crimes can be committed by men of such conventional appearance.’

Every time I consider these perpetrators, my heart thumps loudly inside my chest. When I teach in a lecture theatre, there are usually about one hundred students present. This means that more than twenty-five women attending the lecture have experienced sexual assault. I look out at them all from the lectern and want to weep. How brave they are!

For the countless victim-survivors who yearn for, and deserve, healing, an important truth I always tell my clients is that we can’t heal in isolation. Recovery requires us to share our stories of shame and brokenness. We must also acquire the patience to listen to our inner child’s sorrow and care for her wounds tenderly. Fortunately, the healing I received enables me to offer hope to my clients who feel crushed by their trauma. I tell my clients it won’t always be this painful, that there is hope even in the darkest of times. By being believed and supported they slowly, sometimes imperceptibly, recover.

Frequently enraged when I sit with vulnerable clients, I’m grateful for my rage and consider it my superpower.

It allows me to cope with the countless women who have sat and wept on the couch in my counselling room. If I had a bucket to catch all the tears these women have shed over two decades of doing this work, it would be overflowing, the tears covering the floor of the office. My tears mingle with my clients’ and our grief-soaked tissues would fill a green wheelie bin.

My own experience of childhood trauma fuels my passion to help others and my rage gives me the energy and commitment to help those who have suffered interpersonal violence. I’ve learned to hold anger in one hand and hope in the other, and these two emotions guide me daily, in my work and in my personal life.

We must stop asking survivors to carry the shame.

Below are some free services for victim-survivors:

- 1800 RESPECT

- The Survivor Hub (A peer support group)

- Victims Services 1800-633 063

- Aboriginal Contact Line 1800-019 123

- Blue Knot Foundation 1300 657380