Battle isn’t hyperbole for what Masters experienced to publish allegations about Price, it’s apt. Because of machinations she was unwilling to detail, Masters had to take her story elsewhere to have it published. She faced legal threats, personal threats, the prospect of her sources losing their livelihood for speaking out and needing anonymity.

After the Weinstein story broke, she says the dynamic changed.

“A key source on that, the woman who had this very unpleasant encounter with him, circled back to me and said she was actually ready to go on the record. She had given us a statement before, but at this point she was just ready to go all the way and describe the whole situation and that was a huge difference,” she said.

“If I knew, how did others in positions of authority in the industry not know?” @THR’s @kimmasters on #HarveyWeinstein. #abc730 pic.twitter.com/kftm3WGF8D

— abc730 (@abc730) October 16, 2017

Since then the has been receiving phonecalls about others to investigate and op-eds from experienced television executives who have been years in the business who are “unburdening themselves”.

The path Masters walked in trying to expose Price is not dissimilar to the path victims of harassment walk should they choose to speak up. There are threats and intimidations. Staying silent is far easier than the alternative.

Could Weinstein be a circuit breaker? Might we be at a tipping point, where more victims of harassment are less likely to be suffocated and silenced by shame? Where perpetrators are less emboldened to abuse their power? Less confident their predatory advances will remain unknown?

Certainly the wake of Weinstein has unleashed an unprecedented groundswell of women speaking out about their own experiences of being assaulted.

Jennifer Lawrence, Reese Witherspoon, and America Ferrera are the latest stars to share their experiences https://t.co/Gmet8OlEOQ

— VANITY FAIR (@VanityFair) October 17, 2017

“I was trapped and I can see that now. I didn’t want to be a whistle-blower. I didn’t want these embarrassing stories talked about in a magazine. I just wanted a career.”

Jennifer Lawrence said.

“[I feel] true disgust at the director who assaulted me when I was 16-years-old and anger at the agents and the producers who made me feel that silence was a condition of my employment”.

Reese Witherspoon explained.

“When he came toward me [in a bathrobe], everything changed. I wanted to flee, I was scared. He told me I looked stressed. He said that he thought maybe I could use a massage, maybe I could give him a massage. He began to get angry. I began to get really afraid. He told me that I would make a bad decision if I got out of there. … I pushed him and ran.”

Lauren Holly said.

“Of all the ugly emotions dredged from my own suppressed history, my hardest wrestle has been with the instinctive, acidic jealousy that’s surfaced towards the women who spoke of fleeing Harvey Weinstein, of fighting him off, of saying no. Because when I was a young, powerless woman trapped alone in a rented room with a predator – the scenario seems ever the same – I did not run. I did not say no. I suppressed my disgust for him and for the situation I was in.”

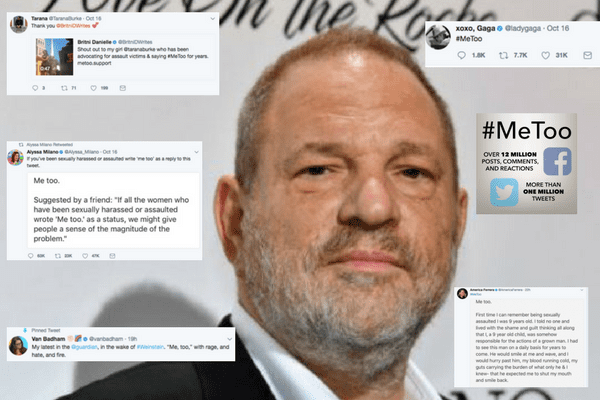

In less than 24 hours, half a million people had used the #MeToo hashtag to detail their own experiences of harassment and assault. Twelve million people posted about it on Facebook and a million on Twitter.

Women of all ages, from all backgrounds, heralding from a variety of industries, have shared their accounts of being assaulted and abused. The confessions illustrate how prolific the experience of assault is and shatters the illusion otherwise.

A moment can create a movement. This is our moment. This is our movement. #MeToo https://t.co/pt6Rh6Lss4

— Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano) October 16, 2017

Sexual assault is not a niche issue that only occasionally claims victims, as the prevailing sentiment falsely suggests. It is not reserved for a certain type of woman in a certain type of situation, as we are so often told. It’s not the remit of humourless women who cannot take a joke or misconstrue friendly banter as something untoward.

It is practically universal, and it exacts a devastating toll.

While the #MeToo revelations don’t amount to a solution the significance cannot be dismissed, as The Atlantic’s Sophie Gilbert observes.

“The power of #MeToo is that it takes something that women had long kept quiet about and transforms it into a movement. There’s a monumental amount of work to be done in confronting a climate of serial sexual predation—one in which women are belittled and undermined and abused and sometimes pushed out of their industries altogether. But uncovering the colossal scale of the problem is revolutionary in its own right.”

And the problem is colossal, of that there is no doubt. And perhaps this is a watershed moment. Perhaps assault isn’t going to be the dirty, shameful secret that victims are burdened with.

On Tuesday evening 730 aired another report that made me consider, even hope, these tides might be turning.

“I think we underestimate just how sticky shame is and how hard it is to speak up.” @JaneCaro discussing sexual assault. #abc730 pic.twitter.com/LYUrvHfnyi

— abc730 (@abc730) October 17, 2017

Sarrah LaMarquand, Jamila Rizvi and Jane Caro comprised the panel interviewed by Stan Grant, to discuss sexual harassment and gender inequality in the workplace. They spoke, not just as talking heads, but as women who, like so many more, have faced it.

Tune in to @abc730 now for Stan Grant's fascinating discussion with @JaneCaro, @SarrahLeM @JamilaRizvi about some of the battles women face

— John Lyons (@TheLyonsDen) October 17, 2017

That this panel took place in prime time, on one of Australia’s most respected current affairs program is not nothing. It is, in itself, a shift.

It might not render the road ahead any easier but it represents the whiff of possibility that women will be heard. And if women are heard, fewer will be shamed into silence.

Is it too much to hope for?