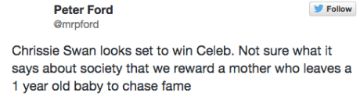

Chrissie Swan looks set to win [I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here]. Not sure what it says about society that we reward a mother who leaves a 1 year old baby to chase fame.

Those 140 characters, tweeted by entertainment reporter Peter Ford on Friday, sparked considerable controversy.

If you’re tempted, even momentarily, to dismiss it as a Twitter-storm in a teacup, resist. If you want to scream political correctness gone wrong or women being frightbats again, resist. If you’re tempted to ask why we can’t have a constructive conversation about a mother abandoning her child to pursue fame, resist.

And listen. Please, listen.

This story is not simply about Chrissie Swan or Peter Ford. It is not about demonising or vilifying one or the other. It is not about seeking fame or reality television and it’s not about a misunderstood tweet. It’s about the very real perceptions and attitudes, particularly around motherhood, that limit Australian women.

Peter Ford gave a very frank interview to Mamamia yesterday where he elaborated on his tweet and the reaction it sparked. His responses simply reinforced the assumptions that were embedded in his tweet.

“I don’t think any of them [the male I’m a Celeb participants] have one year olds and I don’t think we’ve seen them on tv crying about how much they are missing their children and want to leave – and she’s been free to leave since the day she arrived.”

“She’s still chasing fame. She’s gone into the jungle presumably to make a lot of money – there’s no shame in that.”

“I’m not criticising her. She can do what she wants. But I would go and clean toilets before I left a one year old baby. But that’s me. What she does is entirely her own business.”

“I never said for one minute that she’s a bad mother. On several occasions on Twitter I said that I’m sure she’s a terrific mother when people tried to provoke me”.

“What I did say, and I don’t back away from it, is that I personally don’t know how you can do that. I don’t know how you could leave a one year old baby and go to the jungle and have no contact with the baby for eight weeks. That’s not a criticism of her. That’s a criticism of me”

“All I’m saying is: I couldn’t do it. I’m not sure why it’s so terrible; that I’m not allowed to say that. I’m not passing judgement on her; I’m passing judgement on me: I couldn’t do it.”

“I think it’s a totally valid discussion point. I’m not sure why people aren’t allowed to discuss it.”

“Maybe the answer to that question (if I’d put a question mark on it) is a positive one. That the world is such that women can go off and do that. And then men are capable in many cases of running the household and looking after the kids. Why is it automatically interpreted that the answer is going to be a negative one? Or that the question is a sexist one. They’re just frightbats reacting.”

“I do think it is interesting that times have changed. That a woman can go off and do a job. That’s not being critical. That’s just about how the world has changed. For better or for worse. I don’t know why this has turned into a man hating thing.”

“I’m not passing any judgement. I couldn’t go and leave my dogs for eight weeks. But that’s me.”

Ford’s comments are laden with conflicting assumptions.

He would clean toilets before leaving a baby: but Chrissie Swan is free to do what she wants.

He’s not passing judgement but Chrissie writes about her children and volunteered for a reality television program so she has to expect and accept negative judgement.

He’s not being critical but he is questioning a society that could endorse a mother leaving her baby.

The truth is Ford was and is criticising Chrissie Swan and his criticism is steeped in sexism.

If he’d asked how society could reward a parent for leaving a baby, it wouldn’t have been sexist. But he didn’t. He said “mother” and that’s what he meant.

If he’d said “parent” it would be interesting to answer because society has, and still does, openly accept fathers leaving babies and children for periods of time. It is especially welcoming of this when they do so to earn money.

I have never read a critique of a cricketer leaving behind a tiny baby for weeks at a time whilst the Australian team tours the world. The same goes for soccer players, rugby players, cyclists, politicians, and CEOs who routinely spend months’ travelling, leaving small children behind. I have occasionally read about athletes or business leaders returning to their partners for the birth of a child – usually for a few days – and this is celebrated. As is their return to work shortly afterwards.

We don’t criticise those choices because we accept them. We expect fathers to go out and earn the bread and we expect mothers to care for their children and we are sceptical of men and women who disrupt those expectations.

Peter Ford is not alone in his thinking; if these assumptions weren’t so hardwired I would argue that the composition of our workforce and the distribution of paid and unpaid labour in Australia would look very different.

But that’s the crux of the problem which Peter Ford’s comments reveal and encapsulate. This is not merely frightbats reacting for the sake of reacting or mothers jumping up and down because they have nothing else to do or women hating men.

The issue of society’s attitudes towards working women is not hypothetically important. It’s vitally important because work and economic empowerment go hand in hand. Denying or limiting a woman’s participation at work, limits her financial independence and autonomy.

Australian women are legitimately limited in their ability to participate at work. We have a quantifiable problem that is getting worse, not better: the pay gap has widened to a new high, pregnancy discrimination is rife, women’s workforce participation is slipping backwards. These issues undermine the financial independence of women which contribute, in no small part, to issues like domestic violence and homelessness.

Assumptions about motherhood are not solely responsible for Australia’s problem with women and work but they contribute to it. Motherhood is inevitably raised by anyone disputing the small proportion of women in senior leadership roles in many fields, despite women being educated and trained in similar numbers to men. Men and women questioning the legitimacy of a woman putting her earning ability ahead of her children – consciously or otherwise – contributes to a culture that treats working mothers as something out of the ordinary.

Why does that matter? Why can’t we have a valid discussion, as Peter asked, about whether women working instead of caring for children is good? We can. But let’s be clear on the starting point. There are clear and detrimental implications for anyone forgoing an ability to earn an income. Why should mothers, rather than fathers, bear that onus? Why can’t parents share it?

Just yesterday a social media discussion focused on the problem of older women and homelessness and guess which demographic is most vulnerable? Women who haven’t worked and have raised children.

Of course there are plenty of cases where that is not true. But statistically a person’s likelihood of facing poverty in old age is increased significantly when they haven’t worked and raised kids. That is what I would like Peter Ford to contemplate because the alternative is to prescribe women with a pitiful choice. Work like Chrissie Swan has and be condemned for your parenting, or don’t work and increase you chance of being condemned to poverty. Talk about being damned if you do and damned if you don’t.