Did you know that you can generate artificial intelligence (AI) images on Canva now? It’s as easy as putting a prompt into the search box and Canva will wave a magic wand and produce an almost-realistic image for you.

This morning, when I found out about this feature, I let my imagination run wild.

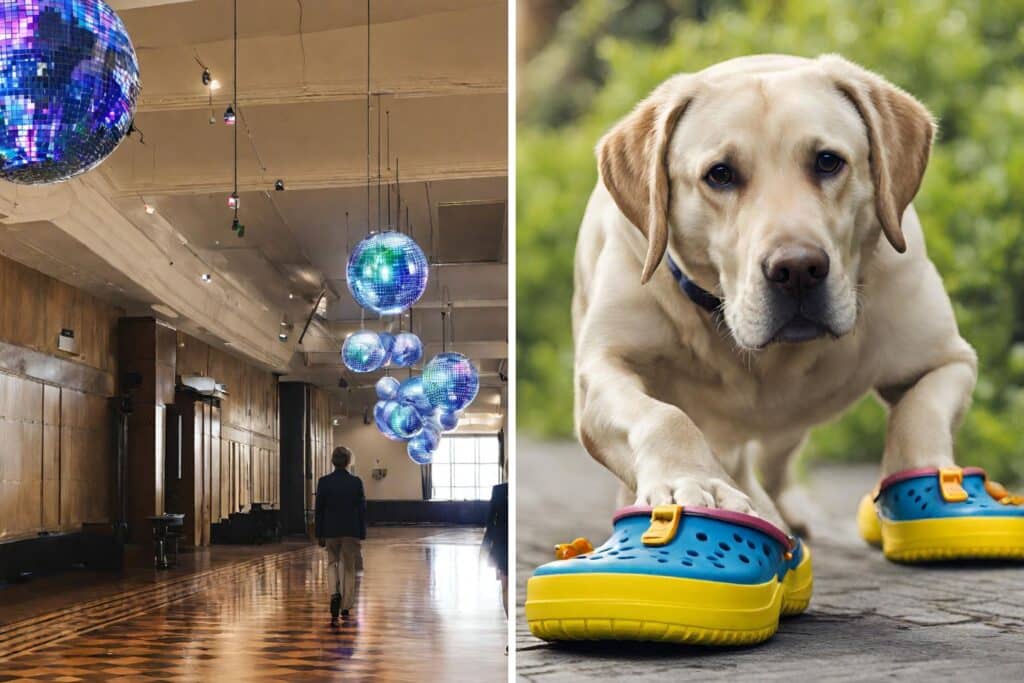

The first prompt I entered was “disco balls in Parliament House”. I just think it would brighten the place up a bit, you know? The image that Canva came back with was everything I’d imagined (Canberra, if you’re reading this, I really recommend hanging disco balls in Parliament House. You’ll thank me later).

My next prompt was “labrador in crocs”. Adorable, right? Canva replied with the cutest image you will ever see.

The final prompt I entered was one simple word: “woman”.

After a few moments, Canva responded. She was thin, had pale skin and piercing blue eyes. Her blonde hair brushed her shoulders and framed a face without a blemish, pimple or wrinkle in sight. Eyebrows, lips, cheeks – it all looked perfect to me.

In a matter of moments, the generative AI tool had given me an image of a woman – that much is true. But it also shone a light on the danger of deep fakes, the inherent biases and the high beauty standards society and now technology places on women.

Deep Fakes

A few weeks ago, the Australian Financial Review (AFR) Magazine published its annual Power issue for 2023. Traditionally, the publication sends photographers out to capture portraits of those who made the top 10 lists for Australia’s most powerful people.

This year, however, the AFR hopped on the generative AI bandwagon and created their own portraits of some people who made this list, including Hollywood actor Margot Robbie and soccer legend Sam Kerr.

Apart from the captions indicating they were AI-generated images, it is clear the portraits are fake. Margot Robbie’s and Sam Kerr’s hands both had odd numbers of fingers, for starters.

“They (the images) are both uncanny and yet slightly unreal,” Matthew Drummond, the AFR Magazine editor, wrote in a piece defending the use of AI-generated images last month.

“All have the distinctive fuzzy texture of AI images, as if they were drawn. Our prompts were very minimal and the output hints at the way AI is learning 21st-century human culture.”

As I discovered, it takes seconds to generate an image that is borderline realistic, which of course raises ethical questions of “deep fakes”, or false videos, images and even voice recordings. Deep fakes can depict high-profile people and can often be used against them.

“Such fakes are set to add a new dimension to misinformation campaigns, and we’re keen not to add to that problem,” Drummond continued in his piece in the AFR.

“Our input images were all selected from what’s publicly available on the web; the fresh portraits that our photographers took for this issue were kept separate.”

The frequency of deep fakes becomes dangerously problematic, particularly in global issues including the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. Just last week, a WhatsApp voice memo which supposedly gave insider information from the Israeli army was discovered to be a fake.

Reuters predict approximately 500,000 video and voice deep fakes will be shared globally on social media this year. However, a survey from 2022 found 43 per cent of respondents admitted they would not be able to detect a deep fake video.

Beauty Standards

I played with another AI tool this morning. The platform I used could take an existing photo and AI-ify the image.

I uploaded a picture of me at my graduation ceremony I took on Monday. I love this photo – it reminds me of a proud, happy, exciting occasion, and you can see it on my face how cheerful I felt at that moment.

Then I clicked the filter “Beautify”.

I decided to use the “glam” setting, maintaining the natural lighting and tidying up the background image a bit. I hit “apply” and waited.

I zoomed in. I looked like me, but kind of different. My skin had lost the red-ish tone I always have and looked the clearest it has ever been. My eyebrows were perfectly shaped. My eyes were symmetrical – I always criticise how wonky they look in photos. The hair on my arms had vanished and my dimple was more pronounced on my left cheek.

Experts have warned how AI-generated images could worsen the problem that people, particularly young people, face when it comes to self-esteem and body image. Already, 73 per cent of people wished they could change the way they look, according to statistics from Butterfly. What’s more, 41.5 per cent of people most of the time or always compare themselves to others on social media.

Analysing the pictures of Sam Kerr, Margot Robbie, the “woman” Canva created for me this morning and even the AI version of me, the threat that AI poses to exacerbated issues of self-esteem and body issues is clear.

The “beautification” of women through AI-generated images, as well as the risk of deep fakes, raises big ethical problems. It’s time that platforms and politicians start thinking up solutions.

Meanwhile, I have a feeling I will find myself looking back and forth between my original graduation photo and the “beautified” AI version throughout today.

For those still thinking about the disco balls in Parliament House, or the labrador in crocs – Happy Friday.