Misinformation spreads. Often, it’s worse during times of heightened crisis, when we’re at our most vulnerable. It impacts how we think and understand climate change. If we’re getting the wrong information, how do we make ethical, informed decisions based on scientific facts?

Evidently, the way we consume information has changed dramatically in the last few decades, and increasingly, self-publishing and social media give way to false or misleading information that can be created and shared at rapid speeds, seen by many before the content is properly fact-checked.

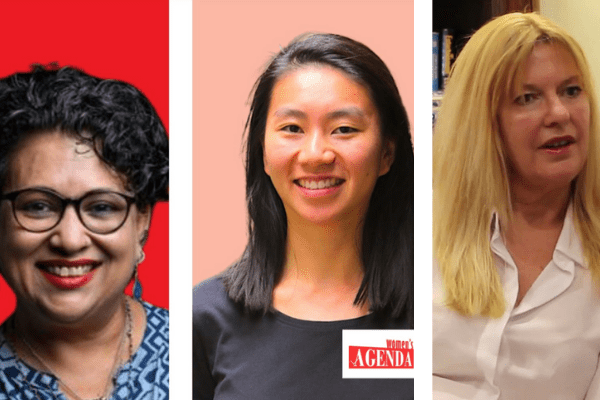

In the fourth Climate webinar created by ActionAid’s partnership with Women’s Agenda, three experts discussed the topic of fake news and how women utilise media as a tool to lead the fight against misinformation and climate denialism.

Women’s Agenda’s co-owner Angela Priestley joined MediaScope advisor Denise Shrivell, climate change psychology researcher, Belinda Xie and Sharon Bhagwan Rolls, head of Shifting the Power Coalition, for a discussion around the impact of fake news and misinformation on our nation’s ability to combat climate change and secure a better future.

“Traditional media consumption tends to be misinformed,” Denise Shrivell said, noticing a mismatch from the experts she saw on Twitter to what she saw on mainstream media.

The more politically engaged she became on her Twitter community (experts and scientists) the less she found herself trusting the information on mainstream media sources.

“I’m careful about curating that community I’ve created on Twitter,” she explained. “There are experts I lean on and I rely on them. They include independent journalists too, who share their views and point to expert articles by others.”

Shrivell lives in Sydney’s north Shore, and is aware she is “living my lived experienced bubbles.” She believes Twitter is an important space where she can engage with individuals outside of her own personal lived experience.

“Twitter is a place where people share their experiences. It’s an active and broad community, and the experts I follow provide opinions grounded in factual information.”

Shrivell believes collective action is required in Australia to combat misinformation, due to the nature of our media landscape.

“We have the most concentrated media ownership landscape in the western world,” she said. “We are more vulnerable when editors and owners are politically aligned.”

Belinda Xie works at the intersection between climate change and psychology. Her research is focused on how people form opinions and make decisions about climate change.

“We look at the insights that can help us understand why we aren’t acting the way we want when it comes to climate change,” she said. “Climate change is a political issue. It’s about people’s values and our identity. It’s a social issue and it’s a cognitive issue. All of this depends on the information we’re exposed to.”

Xie went on to explain the Continued influence effect, which is a term that refers to the way that falsehoods persist in our thinking.

“Misinformation is the inaccurate or false information that may or may not be deliberately deceptive,” Xie explained. “But it’s difficult to correct their wrong information. Misinformation serves a purpose. When corrected, the gaps are not filled.”

“Misinformation can also fit in well with what people believe. It’s often designed to be simple and compelling. Evidence based information is complicated and takes longer to work through. Misinformation often goes unchallenged.”

Sharon Bhagwan Rolls, who was calling in from Suva, Fiji where she is based, said that she wants to see climate justice evolve from the increase of representation of women and globally in media monitoring projects.

“From my point, I think we need to better inform ourselves about climate science and what’s going on in the Pacific Island communities, where climate change is affecting our identity, our history and our heritage,” she said. “We need to get better at broadcasting these stories and listening to these communities. What is the impact that’s taking place in their lives? We’re talking about future generations.”

Belinda Xie believes that Australia is particularly stubborn in implanting climate change solutions. “We see a conservative government who are more about market based interventions,” she said.

Her research looks at the impact of misinformation on climate change and distinguished the different variables in measuring how people’s opinions on climate change are shaped; by their age, political party, social norms around them, and whether they’ve experienced extreme weather events.

“We can share emotional stories, explain why your care can help other people accept that it’s real threat,” Xie said. “People’s belief in statements is counter balanced to emphasise solutions and feasibility. We need people to talk about how solar energy is cheap, that in the renewable industry there are a lot of jobs, how easy it is to change super funds, how to compost. We need to make solutions easier so people can see how easy it is.”

“The way people act and think around you will influence the ways you act,” she remarked. “We each have power and influence of friends and family and we influence how they act and shift their behaviour.”

Shrivell too, believes part of that involves being more conscious of everything you do online and offline.

“There are organisations that are asking marketers not to work with clients that promote fossil fuels now,” she said. “Also, be more conscious what your superannuation is funding. Be smarter in investing and know what you’re buying.”

She also believes it’s important to “curate your community on Twitter and follow people who are trusted.”

Sharon Bhagwan Rolls worked in broadcasting for a number of years and didn’t hear voices of women. This prompted her to create platforms through the use of radio and technology so that women may share their stories.

“We wanted to share information to women in our communities and also challenge the status quo in terms of content,” she said. “To use SMS technology means we’re quickly getting information out to women especially in rural areas. The technology didn’t have them rely on access to data or credit in phones.”

Rolls created the Women’s Weather Watch information-communication system which has so far reached over 77,000 people and has in the past few months, provided communities with information on best ways to prepare and respond to the COVID-19 crisis.

“How do we get information from and to women?” Rolls asked. “We need platforms that share their insights as well as give them information that affect them.”

Book Recommendations from this discussion:

Body Count by Paddy Manning

How to Talk About Climate Change in a Way That Makes a Difference by Rebecca Huntley