Disney’s new The Little Mermaid has been called ‘inauthentic’ – but fairy tales have always been repurposed across cultures, Michelle Smith, from Monash University in this article republished from The Conversation.

Disney’s forthcoming live-action adaptation of The Little Mermaid has sparked an astonishing backlash. The trailer for the 2023 film was met with millions of dislikes on YouTube, seemingly because the mermaid is played by Halle Bailey, a Black actress.

The 1989 animated Disney film, on which the upcoming film is based, featured a red-headed mermaid named Ariel (and a singing crab with a Jamaican accent). The implication of much of the recent criticism is that a Black mermaid is not “authentic” to The Little Mermaid fairy tale.

But fairy tales are continually retold in new ways over time.

Hans Christian Andersen’s literary fairy tale is radically different to the 1989 film. He was a bisexual social outsider who struggled to express his desires. And his The Little Mermaid was not the happily-ever-after romance Disney fans are familiar with, but a tale of torturous unrequited love – which he worked on while a man he was infatuated with was getting married.

The first Cinderella was Chinese

Outrage over fairy tales crossing cultural and racial boundaries is misguided. Variations of most popular tales are found in multiple cultures, and familiar tale types have a history of circling the globe. The way they’re told has adapted, too: from being shared orally, to literary versions (from the 17th century), and now film, television and games (from the 20th century).

Indeed, the very reason fairy tales have endured is because they are continually retold in new ways, to suit changing audiences and cultural norms.

The first recorded Cinderella variant, for example, is Yeh-Hsien, from China. It was first published around 850; while Charles Perrault’s Cinderella, which influenced most adaptations we know today, was published in 1697. Yeh-Hsien does not have the aid of a fairy godmother; instead, she wishes on the bones of a fish. If fairy tales should only “belong” to the first culture in which they were ever told or written, then it would be logical to suggest we should only depict Cinderella as Chinese.

The story of Yeh-Hsien is the first recorded variant of Cinderella.

Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid

Disney’s animated adaptations, beginning with Snow White in 1937, have come to define our cultural understanding of fairy tales. It’s one reason why we’ve lost our cultural awareness of the diverse origins and traditions surrounding these tales. And these films, aimed at a family audience, sanitise earlier fairy tale variants – which were often more gruesome and disturbing than their Disney adaptations. https://www.youtube.com/embed/GC_mV1IpjWA?wmode=transparent&start=0 The story of Disney’s Little Mermaid, Ariel, is very different from Hans Christian Andersen’s original.

Unlike the Disney films, Andersen’s The Little Mermaid is a tragic story of suffering and extreme sacrifice. P.L. Travers, the author of Mary Poppins, wrote about her dislike of the mermaid’s protracted agony and found Andersen’s “tortures, disguised as piety” to be “demoralizing”.

Many of Andersen’s protagonists are small and delicate figures who arouse our sympathy. This frailty can be due to being poor and uncared for, as in The Little Match Girl. Or it can result from characters who are unable to move without difficulty. The tiny Thumbelina must be carried from one location to another. And the Little Mermaid walks with the sensation of metal blades piercing her feet with every step.

The Little Mermaid is also a prime example of Andersen’s focus on female sacrifice and suffering. For a start, she has her tongue cut out by the sea witch and is made mute. And she maintains her delicate femininity with her “lovely, floating” walk on her hard-won human legs, despite the severe pain that is the cost of her bargain.

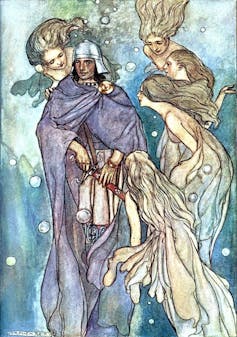

The mermaid saves the Prince on two occasions. First, she risks her life to rescue him from a shipwreck. Andersen’s fairy tale is not a love story, however, because the Prince never romantically desires the mermaid. He is impressed by her devotion but treats the mermaid like an animal or a child. He even gives her “permission to sleep on a velvet cushion at his door”.

The ultimate self-sacrifice of the Little Mermaid is evident when the Prince marries another woman and the mermaid holds the train of her wedding dress, while thinking only “of her death and of all she had lost in this world”.

The sea witch had promised that if the mermaid could make the prince fall in love with her, she would gain an immortal soul. If not, she would die of a broken heart on the first day after his marriage to someone else – and become sea foam on the waves. When she is faced with the choice to kill the Prince and rejoin her family in her mermaid form, she sacrifices her own life instead.

Andersen as outsider

Andersen’s sad personal life unavoidably influences how his stories of downtrodden and pitiful characters are interpreted. In the case of the Little Mermaid, there is a close connection between the writing of the story and Andersen’s own feelings of isolation and rejection.

Andersen was a social outsider who never married – and potentially never had sex. He did become infatuated with both men and women and is therefore understood as bisexual. Yet he struggled to express his desires, an issue related to a series of complex psychological problems.

One of the men Andersen loved was his friend Edvard Collin, who did not return Andersen’s feelings. Biographer Jackie Wullschläger notes that The Little Mermaid was written “at the height of Andersen’s obsession with and renunciation of Edvard Collin”. When Collin’s marriage to a woman was held in August of 1836, Andersen intentionally remained on the Danish island of Funen in order to avoid the wedding. There, he continued to work on The Little Mermaid.

It is possible to view the Little Mermaid failing to gain an eternal soul through marriage to the Prince as Andersen rejecting the idea that immortality must depend on love being reciprocated. As Wullschläger suggests, Andersen likely equated himself, a bisexual, with the mermaid’s understanding of herself as a different species to humans.

Andersen wrote that he deliberately avoided the convention found in other mermaid fiction, such as Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s Undine (1811), in which human love enables the acquisition of a soul:

I’m sure that’s wrong! […] I won’t accept that sort of thing in this world. I have permitted my mermaid to follow a more natural, more divine path.

Andersen’s tales frequently promote his Christian religious ethics. The path to salvation with God that Andersen maps often entails a cheerful embrace of pain, suffering, or humiliation. Maria Tatar comments that Andersen’s protagonists embrace death “joyfully”. They “reproach themselves for their sins and endorse piety, humility, passivity, and a host of other ‘virtues’ designed to promote subservient behaviour”.

Most of Andersen’s protagonists are female. Fairy tales in the 19th century, such as those of the Brothers Grimm, commonly sought to direct the behaviour and morality of girls. In the case of the Little Mermaid, her harsh treatment and ultimate fate can be understood as punishment for her sexual curiosity in pursuing the Prince. It’s also a caution against attempting to leave the undersea home where she belongs.

The conclusion of Andersen’s tale transforms the Little Mermaid into sea foam and then a “daughter of the air” who may gain a soul after 300 years of compassionate, self-sacrificial behaviour. The moral educational function of fairy tales is especially evident in this ending. Child readers are informed their own good acts will shorten the length of time the Little Mermaid (and the other daughters of the air) must wait by one year, while bad acts will lengthen their wait.

Diversifying and adapting fairy tales

Disney’s original, animated The Little Mermaid departs radically from Hans Christian Andersen’s published fairy tale. Some of these changes reflect developments in ideas about the purpose of stories of children. Young characters undergoing extreme self-sacrifice and unhappy endings now rarely appear in stories for children.

Disney’s transformation of a story of salvation and religious devotion into a straightforward romance is but one example of how fairy tales lend themselves to retelling in new contexts. The live-action adaptation starring Halle Bailey, which seeks to make children of colour feel represented in fairy tales, is one more iteration of the story.

This attempt to diversify fairy-tale adaptations builds on the queer history of The Little Mermaid. The story is already understood as having parallels with Andersen’s bisexuality – and the experience of transgender people. The most important UK organisation for supporting transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse young people, for example, is called Mermaids.

It’s unsurprising that outsiders of all kinds connect with a story about a mermaid who cannot fit in the human world she desperately wishes to belong to. Whether that’s a beloved author in 19th-century Denmark, or an African American girl today.

Michelle Smith, Senior Lecturer in Literary Studies, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.