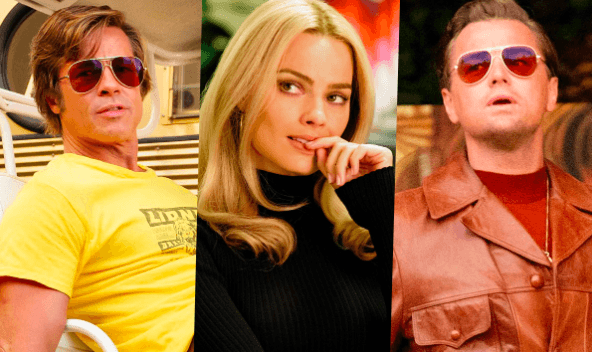

I’m not a Tarantino aficionado. I haven’t even seen the entire Kill Bill series. But I’m a sucker for huge Hollywood stars so the lure of Margot Robbie, Brad Pitt, Leonardo DiCaprio and Al Pacino, on screen together, seemed too good to miss.

Historically though, I’ve avoided Tarantino’s films because of my distaste for violence on screen.

It’s worth noting, of course, that Tarantino is far from alone in depicting violence in his films. Some of the top grossing films so far this year include Shazam! Pokemon Detective Pikachu, John Wick: Chapter 3 — Parabellum, Us and Avengers: Endgame and all of them have a measure of violence.

Casey Affleck has a film coming out about women being wiped off the face of the earth, and his brother Ben has one about the rape of a woman that is actually about two men driven by revenge. All these films centre on male characters reproducing some level of violence with women the collateral damage. Tarantino has certainly structured his film career around the premise.

His first film, Reservoir Dogs, contained no female speaking parts. In both Kill Bill and Pulp Fiction, Uma Thurman’s characters were repeatedly subjected to violence. While filming Kill Bill, Tarantino pressured Thurman to perform a dangerous stunt that resulted in a crash, where she sustained permanent damage to her neck and knees.

In The Hateful Eight, Jennifer Jason Leigh’s character is pulverised in a torture scene so vile I could not sit through it. Roy Chacko wrote in The Guardian recently about Tarantino’s predilection for extreme violence towards women. He wrote: “[His] interest in savage violence against woman is a common thread in almost all his films.”

In all his films, men are the winners, women are the losers.

In Tarantino’s films the glorification of male power is always at the expense of female suffering. His latest film centres on two male characters (no surprises there) and continues to normalise the subordination of women. Critic Noah Berlatsky described the film as “uncomfortably vacuous”.

Margot Robbie, who plays Sharon Tate, is treated by the director as “nothing more than a pretty image and has little dialogue.” What does it say about us as a society that these films which celebrate violence and the subordination of women have such appeal; films that almost always centre on men pillioring the world on their terms?

Films have the power to shape behaviour, attitudes and beliefs so exploitive narratives that capitalise on destroying a woman’s agency are problematic. So too white characters casting minorities to the side.

But the male ‘genius’ filmmaker can get away with anything: Quentin Tarantino, Lars Von Trier, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and David O. Russell have all been accused of abusing their subordinates. Why do men who create ‘art’ set terms for themselves outside of common law?

As Imran Siddiquee wrote in 2017: “Many of the ‘greatest’ artists in our most influential visual art form continue to be celebrated for their own obsessive, often abusive exercises of power and control.”

I am hyper-vigilant about the way female characters are portrayed in film. We often internalise what we see. It doesn’t mean you’ll see me plundering through George Street in a stolen Chevrolet Corvette after seeing The Fast and Furious. The influence is far more subtle.

Recently, it dawned on me that many of the films I watched and loved as a child all had something in common. The Matrix films, The Mission Impossible series, Bourne, Die Hard, Saving Private Ryan, Face Off, The Fifth Element. These were all about men – men were the ones doing things, having batshit crazy adventures, saving the world – and women were on the periphery. They were watching, being the sex objects, being mute and beautiful, not necessarily doing anything meaningful.

The men in these films all had human lives. Complicated, confusing and chaotic lives. Not the women. What happens after decades watching stories where women are uncomplicated, one-dimensional ornaments? Where they fall away to the side, or die off or simply serve as the punchline to all the jokes?

It says women don’t need to be treated with the same respect as men. It sends a message that women are not as important as men. That they don’t need to be taken seriously. And it feeds into our ongoing failure, as a society, to recognise the full humanity of women.

So many of these highly-watched films tell us that a woman’s role is insignificant. Too often the degradation and defeat of women is the triumph of men. Male power is contingent on the losses suffered by a woman. Women in these films are often put in positions where they need saving, where they are victimised, but in the end they attach themselves sexually and romantically to these men. It’s not difficult to understand why culturally we can’t always distinguish between female pleasure and female suffering.

If you watch all these films as an adolescent and you are not shown different ways of being, women end up perpetuating what they have seen. If no one shows you how to find what you truly desire, then you start to desire what other people desire. There are countless films that follow that same algorithm of placing women to the side and subjecting her to the terms set by men.

It feeds into the #MeToo movement and explains why it’s easier for a lot of us to believe that a man’s career matters more than the hypothetical losses of a woman he might have harmed. A.O Scott said The Hateful Eight was “an orgy of elaborately justified misogyny.” Welsey Morris called Django Unchained “absurdly violent.” And yet they were celebrated.

On the subject of race, Welsey Morris observed that, “Tarantino’s films have come to understand black people as mighty movie types, rather than as human beings”.

I feel it’s the same for women. Women, in his films, are not treated as human beings. They’re not given the depth, scope, validity or value as the straight white male characters.

On the 50th anniversary of Sharon Tate’s violent murder, Hollywood has sought to make some money off of this by releasing three films about her murder. All three stories are written and directed by men. Of course. A woman’s life and death have been taken from her and repurposed for commercial value and appeal. In too many films, particularly Tarantino’s, nobody seems to care what the women wanted. The worst part is that awful reality isn’t limited to ‘art’.

The New Yorker’s film critic Anthony Lane sums it up perfectly in his review of Tarantino’s latest film:

“Two things alone freaked me out. One was the sudden, insane burst of brutality that is inflicted by men upon women. And the other was the reaction of the people around me in the auditorium to that monstrosity. They laughed and clapped. No one was surprised. The jitters have become a joke.”