The Coalition Government’s response to the economic fallout of COVID-19 – namely its focus on a “blokecovery” to what is, by all accounts, a “she-cession” — has led some to speculate that the prioritisation of men and male-dominated industries in stimulus measures will not only prove bad economic and social policy, as numerous economists have already warned, but bad politics. Women voters might punish the Coalition at the next Federal election.

Recent events have prompted a lot of questions:

Will some of these decisions exacerbate the Coalition Government’s already well known “woman problem”? Will the so-called “women’s vote”, which was meant to be decisive at the last Federal election and then wasn’t, finally come into play? Will women’s anger and frustration at seeing a male-dominated government and male dominated decision making bodies sideline their interests, including the National COVID-19 Coordination Commission, be front of mind when they cast their next vote?

It’s complicated, leading experts tell Women’s Agenda.

Read more in this series: Fears of a ‘Mum-cession’: experts warn of pandemic motherhood penalty

It was “game on” for the women’s vote

Ahead of the last Federal election, it was thought to be “game on” for the women’s vote.

In a September 2018 piece for The Guardian, veteran pollster and Executive Director of Essential, Peter Lewis, declared that if the Liberals wanted “to have a chance at the next election, they must close the gender gap”.

What Lewis and others were referring to was the long-term trend in male and female voting habits, known as the “gender gap”, a trend that has been well documented in the regular Australian Federal Election Study coordinated by Australia National University.

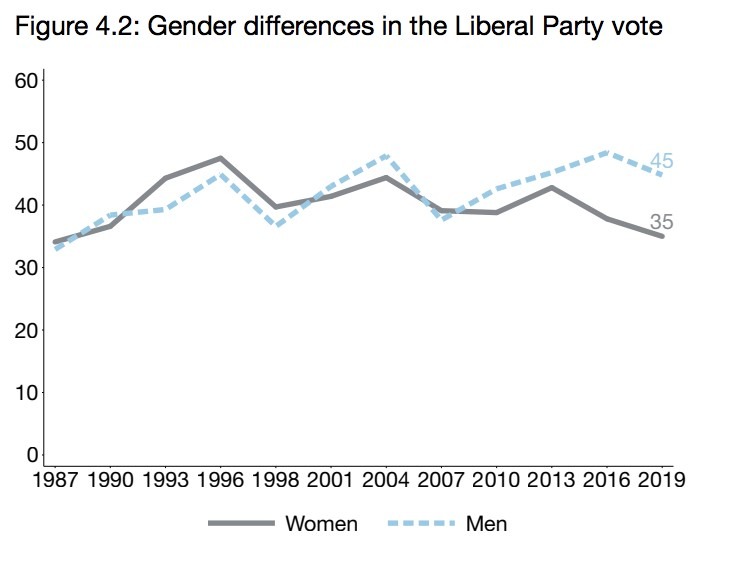

At the 2019 election, while 45% of men gave their first preferences to the Liberal Party, just 35% of women did. Women were marginally more likely to vote Labor at 37%, compared to 34% of men.

That widening “gender gap” (see chart below), with men becoming much more likely than women to vote for the Liberal Party, has reversed over time and deeply troubled the Liberal Party. Back in the 1990s, women were slightly more likely to vote Liberal than men. We saw the opposite in the Labor Party vote: men were slightly more likely to vote Labor than women.

Growing concern about that “woman problem” prompted the Conservative think tank the Menzies Research Centre to compile a 2017 report, “Gender and Politics”, aimed at fixing it.

Against that backdrop, there was open mutiny in the ranks of the Liberal Party’s (relatively few) women, who increasingly made their disquiet with the male dominated status quo known via protest resignations and colour-co-ordinated signs of defiance.

In that piece about the “gender gap” for The Guardian, Lewis declared that “the impact on gender on the electoral pendulum is real and it is huge advantage to the ALP, which has diligently begun releasing policies to entrench that advantage.”

“Policies, it should be noted, like topping up super payments for women on parental leave, that are evidence of a deeper understanding of the lived experience of working women,” added Lewis.

So, in the famous words of Hillary Clinton, “What happened”?

“The election wasn’t ultimately about that,” Lewis, with the benefit of hindsight, now tells Women’s Agenda. “Labor, for a whole bunch of reasons, allowed the election to be around economic risk, not around those issues.”

“There was no gender gap, it was down to virtually nothing,” says Professor Ian McAllister, of Australia National University, who coordinates the Australian Electoral Survey and is one of the country’s leading authorities on voting trends. “It looked to me like there was not much there.”

But why was there no “there” there? Opinions vary.

“We’ve got a very utilitarian political culture, rather than a rights-based culture,” says McAllister. “So, people tend to view the state as something to deliver goods and services, benefits, regulation, whereas people in Britain and the US would see the state as something that delivers personal freedom and human rights…so it’s largely a question of political culture.”

“People also tend to think that ‘economic’ voting is largely to do with the person’s individual economic circumstances (the household economy) and it’s actually not,” adds McAllister. “I’ve been telling politicians this for the last 30 years and nobody believes me… they are looking at how policies are going to affect the national economy.”

For Associate Professor of Politics, Media and Philosophy at La Trobe University, Andrea Carson, who contributed to a new book, Morrison’s Miracle, about the 2019 Australian Federal election, the mainstream media was part of the problem and complicit in marginalising gender issues. “Labor was pitching some female friendly/ family friendly policies, but they didn’t get traction with the media,” she says.

“The front-page coverage was on topics that fit very much with the Coalition’s agenda…around tax, around the unpopularity of Bill Shorten, and around other economic policies that the Government was promoting,” adds Carson. “The issues — health, education and childcare, issues that Labor is typically stronger in (and that are, arguably, more relevant to women) — hardly made the front pages at all… they were conspicuously absent.”

For Lewis, it was also a failure to capitalise on gender related concerns with a more “unifying” narrative. “I reckon that if you just run on gender, you’re dividing,” he says. “You have to find the unifying narrative, not the dividing narrative to make it work.”

“The trick is not to run a ‘woman facing’ strategy, but a strategy that women want to be a part of because it speaks to them,” adds Lewis.

Will women be the rainmakers at the next Federal election?

Since COVID-19 plunged Australia and the world into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, the Coalition Government has not only been grappling with a once in a generation public health crisis, but an economic crisis: how to get the economy back on track and people back into jobs?

But despite the fact that women are over-represented amongst the COVID-related job losses (5.3 % compared to 3.9 % for men) and lost working hours (11.5 % compared to 7.5% for men), a string of early support and stimulus decisions by the Coalition that prioritized men whilst ignoring the reality of how COVID disproportionately impacts women caused alarm.

JobKeeper was not uniformly applied. The industries that missed out, such as the arts and academia ,and those characterised by precarious or casual work, like retail and hospitality, tended to be female dominated. Stimulus packages, such as the HomeBuilder or the Defence Force upgrade announcement, favoured disproportionately male dominated industries like construction and the military.

And then there was the “snap back” to the previous childcare system, which saw temporary fee relief for parents rolled back and the female dominated early childhood workers the first, and thus far the only, sector to lose access to JobKeeper. What’s more, up to a third of families indicated that they would struggle to pay the fees in the new economic reality.

In the midst of the pandemic, some – and it seemed momentarily the Coalition Government – realised how vital support structures like early years education are in enabling women to work — many of whom were now deemed “essential”. Had the penny dropped that the absence of such support structures could have devasting consequences for women’s workforce participation and long-term economic security? It was not to last.

Even when Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced the $250 million lifeline for the arts, he couldn’t resist the temptation to emphasize a male angle. Look guys: tradies can build the scenery!

And then the Coalition added to its long and illustrious history of female unfriendly gaffes — adding insult to the more substantive gender related policy fumble injury. The Prime Minister suggesting that women should be delighted to give birth next to an “upgraded” highway instead of a properly equipped regional maternity facility reminded many of his timely pronouncement on last year’s International Women’s Day that women should not rise “at the expense” of men.

Many women were, to put it mildly, not impressed. Fury erupted on social media. But will that fury be sustained and show up at the ballot-box?

Andrea Carson is not optimistic. “How this plays out politically depends on whether these issues get elevated…whether the Labor Party and the Greens promote them and on how they get amplified through the media,” she says. “If 2019 is anything to go by, they won’t get picked up by the mainstream media.”

McAllister, on the other hand, can foresee a scenario where the stimulus decisions hurt the Coalition, but not necessarily because of a gender specific backlash. It would be more to do with the fact that such decisions could prove poor economic stewardship, highlighting the Government’s antiquated view of what a modern economy is and what it actually does. That includes recognition of the importance of the women dominated service and caring industries.

“It’s entirely possible that the way this is packaged and presented — the narrative that surrounds it — could damage the Government in the sense that this would seem to be damaging the national economy,” he says. “But it’s worth noting that nobody has experienced any of this since the late 1920’s/ early 1930’s — we’re in uncharted territory.”

Peter Lewis also believes that an agenda or debate that touches upon these issues without making them exclusively about gender would be more likely to influence voters, including the increasingly important female voters. “A (modern) family agenda and a modern caring economy, and you start to get there,” he says. “The opposite of that is a trickle-down economy that works for corporates or a ‘bloke-covery’ that works for some men, but not for everyone.”

Carson concurs that the current situation is unprecedented and unpredictable, but she believes it is a very interesting time to explore these very important questions. “We’re in the middle of the pandemic, and it’s very hard to have long-sightedness when you’re trapped in the middle of something that’s so intense,” she says. “Whether this translates to how women vote at the next election remains to be seen.”

Kristine Ziwica is a regular contributor. She tweets @KZiwica

This is part two of a series of pieces Kristine Ziwica is producing on how COVID-19 is impacting women in Australia. The series is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.