A couple of weeks ago I wrote about my experience trying to teach my own children for a year while we travelled around Australia in a caravan. I was at pains to point out that I didn’t want to compare that experience with the difficulties of trying to educate children at home during the COVID19 pandemic, but merely to provide an opinion, as a teacher and parent, of what learning children really do need at the moment, and what might be fine to leave alone.

Part of my reasoning for writing the piece was that I knew that already, by mid-April, many parents were feeling overwhelmed by the amount of work schools were asking their children to complete. I believe this large amount of work is being supplied partly because teachers are also feeling overwhelmed and under threat.

They’ve already been called “babysitters” by the Prime Minister Scott Morrison and subject to enormous community angst about whether their workplaces should be open for all children right now, and must feel that any complaints or fears they have about returning to rug-rat central comes across as them whinging, or being unnecessarily afraid.

And yet, Coronavirus cases are still popping up in schools, and evidence of whether (and how much) children catch and transmit the virus remains unclear.

Because teachers are being made to feel they need to justify their jobs even though they don’t have most children in their classrooms, I believe many feel they need to make sure the work they send home must be comprehensive, even OTT.

They’re not doing it to stress parents, but because they themselves are scared, and under the direction of school managers who are still fighting for funding and – in the case of private schools – for the continuing payment of fees.

None of this is the fault of teachers or schools: they’re doing a magnificent job during an unprecedented crisis. But it does mean parents are getting the rough end of the pineapple in terms of what’s expected and what they can realistically achieve: especially for the enormous number of parents also trying to work from home themselves.

For many parents, my previous piece was welcome, as it explained that they should relax and just do the basics, as children will be fine and will catch up later. However, I noticed there were still many parents who didn’t want to take that advice as they seemed unwilling for their kids to fall behind even by a couple of weeks while at home.

In a few forums, I was spoken to harshly by parents who were upset I’d countenance, even for a second, that their children might not be keeping as up-to-date as possible. They did this even knowing that all children are in the same boat so won’t, by and large, be falling behind each other.

I wondered why this hostility and anxiety in so many parents existed, combined with their insistence on getting through every single page of what teachers were sending home.

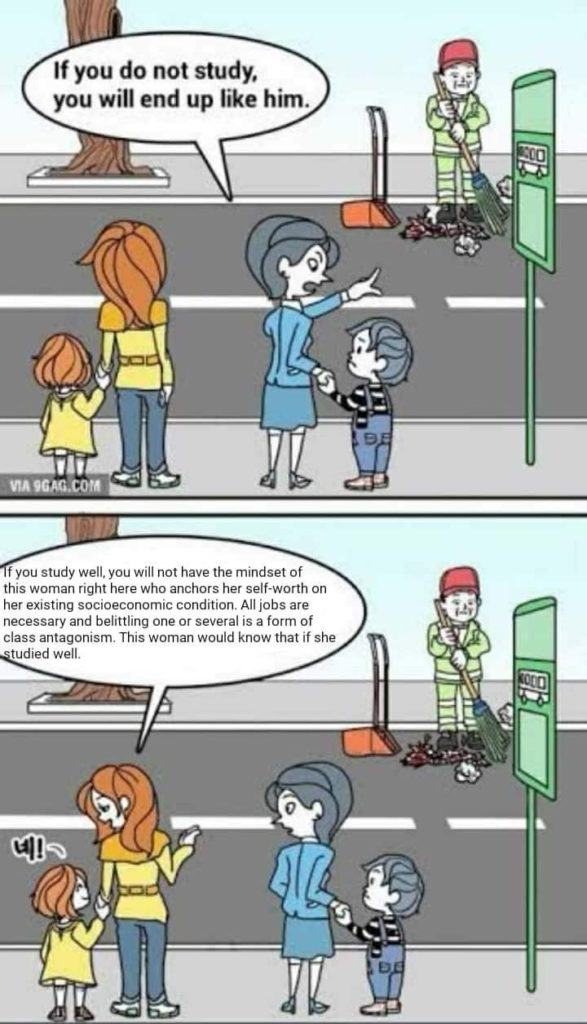

And then, I saw this meme.

At first glance it’s magnificent, of course, and most of us would thoroughly agree with it. But at a second (or third) glance, it stuck me how it’s intrinsically at odds with how many parents and carers are behaving right now. Because on the one hand we’re all praising the many lower-paid workers keeping our communities and countries running as smoothly as possible, while at the same time we’re desperately trying to ensure our children are well-educated enough not to join their ranks.

This struck me, when I considered it, as the rankest form of hypocrisy. It’s difficult, in my view, to feel grateful to the supermarket workers, truck drivers, dock workers, tradies, call centre staff, online shopping packers, hospital cleaners and all the other people keeping Australia running right now, and yet simultaneously be horrified about an interruption to your child’s education.

I don’t believe many parents are even aware they’re doing this, but, in essence, panicking about your child missing a few months of school may be a sign that you’re upset by the chance of them not getting a great ATAR score and a place at the best university.

And if you’re doing that while also relying for your very life on those without that education, who put the food on your table and electricity in your cables, it might be something to examine.

I don’t expect this to be a popular view, and I suspect many parents will be angry at the suggestion. But in these recent decades when children’s achievements seem to be less and less about their own happiness and worth to society and more and more about winning in the stakes of parenthood by having the most accomplished child, these are issues we urgently need to face and discuss.

It’s the supermarket personnel and truck drivers and hospital cleaners who are keeping the world turning right now: not the lawyers, stockbrokers or finance brokers.

Nor is education any proof of a happy life: suicide rates are at their highest amongst medical workers and have been for years, and vast numbers of the highly-educated drop out after their expensive educations to go back, with relief, to a simpler life.

Perhaps if you leave your child alone to play, to focus on learning what they want to learn and slowly adapt to this strange new world (as we all are) they’ll turn out just fine.

Perhaps one day, you’ll be prouder of your child who kept a hospital safe as a cleaner than of the one who became an economist. Perhaps that might help us move towards a world where we value everyone regardless of their education or income status. And perhaps – god forbid – we’d value the artists, musicians, dancers and actors who are currently excluded from much of the financial support on offer in Australia yet will be sorely needed in the future to help our hearts and emotions make sense of this extraordinary new planet.

Don’t worry that your child isn’t top of the class. Worry that they’re a good person with an important contribution to make. Because in COVID times, this is the example we all need to set, and the problem we all need to solve.

Your kids will be fine.

PS: Anything said here isn’t meant for all children, parents, or situations. There are children who do require consistent ongoing learning with as few disruptions as possible (and for most, I understand face-to-face schooling is still operational). There are children vulnerable for a number of reasons and for whom the structure of a school routine is critical. There are children who don’t have the equipment or learning space they need at home. Most of these kids should still be in formal schooling, and many are. But there will always be individual cases and situations which can’t be covered in this general outline.