In Australia, conversations about domestic violence are being conducted on a daily basis. Research and education continue to address the need to raise awareness of women’s health and reduce violence against women, but how much attention is being given to the ethnic nuances around the issue?

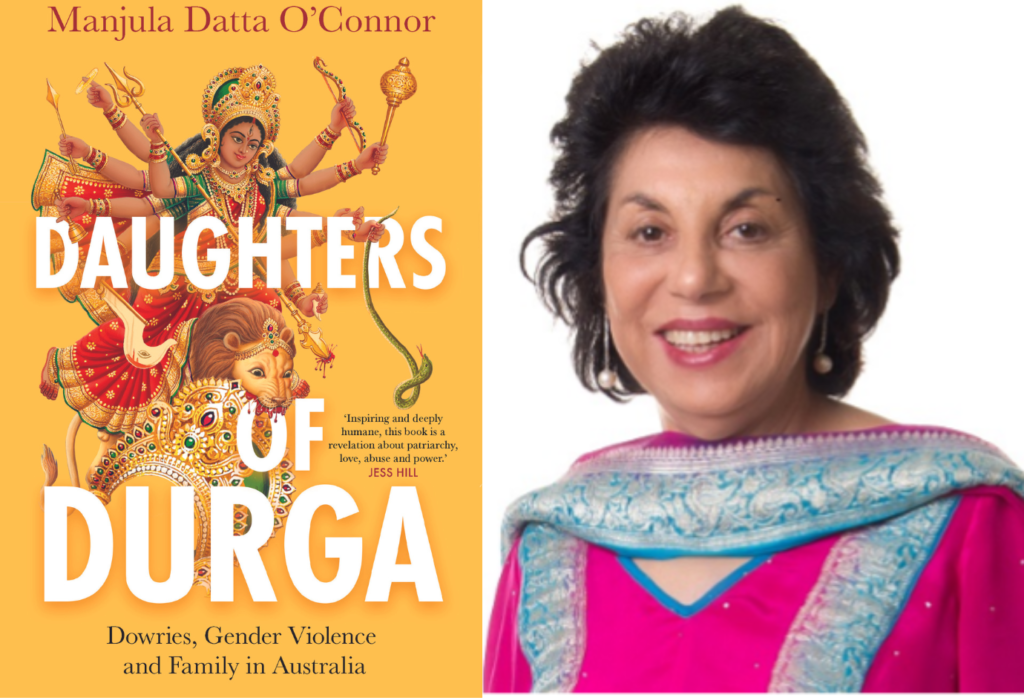

Melbourne psychiatrist and author Manjula Datta O’Connor has written a book that gathers her decades of research and field work as a specialist in migrant women’s mental health, complex trauma and family violence.

We sat down with the esteemed writer to ask her about the issues she explores in her book, “Daughters of Durga“, published last month by Melbourne University Press.

Why did you write this book? Was it born out of anger? Curiosity? Responsibility?

It was born out of several motivations. Some were internal forces. After reading Amartya Sen’s book The Argumentative Indian I felt a profound sense of shame and guilt having learnt about the extent of suffering of Indian women captured in the book.

The problems these women faced began before birth: from sex selective abortions, to female infanticide, to poor care of young girls and to dowry murders. Life as a widow would be tough. She would be shunned by society and not expected to remarry, while the man could.

Indian women have the highest rates of suicide in the world. I felt shame for not knowing how my compatriots were suffering. In 2008 I noticed stories my patients were telling me of dowry abuse, physical violence and coercive control. I was angry and frustrated. A solution had to be found. But it could not be done without exposing the problem.

A series of murders and suicides in our community compelled me to speak out in 2012. The Indian consulate became upset about it. But I felt the problem could not and should not be swept under the carpet.

The typical pattern of dowry extortion was becoming very clear to me. When the dowry-related murder of Deepshikha Godara in 2015 was not identified as dowry murder in the coroner’s report, I knew I had to do something. Deepshikha and her family back in India had to endure ongoing demands for cash. In Melbourne Deepshikha herself was suffering ongoing abuse, violence, humiliation and criticism for years. She eventually took a decision to separate. As a final act of control her husband murdered her.

This story led my NGO, the AustralAsian Centre for Human Rights and Health, to campaign against dowry abuse in Australia. We lobbied the state and federal government MPs. We met the then Premier Ted Bailleu, and Premier Daniel Andrews announced the Royal Commission into Family Violence in 2015.

That gave us a perfect opportunity to make a submission to have the Family Violence Protection Act changed in Victoria. The impact we had in our campaigning saw the act changed to include dowry abuse as an example of family violence.

What made you decide to become a clinical psychiatrist?

My first choice in fact was obstetrics & gynaecology, but in my day, it was male-dominated profession and there was only one registrar position available. As a doctor trained overseas I stood little chance. Psychiatry was my second choice and l loved it.

During my training and later as a qualified psychiatrist I have learnt so much from my patients. They inspire research and innovative treatments. The intensive therapy sessions often give me insights into the true needs of the community. All of this informs my ideas for prevention programs run by the AustralAsian Centre for Human Rights and Health. All our programs thus far have received state or federal government funding.

What was the most challenging part of writing this book?

Family violence is a very complex, multi-layered problem. But including the migration and cultural complexities in this discussion made the task even harder. I wanted to demonstrate that Indian women have a heritage of strength and resilience endowed by their culture; they do not come from a position of deficit, but strength.

So the chapters in the book are arranged to first show the strength of our rich, wise and knowledgeable 5000-year-old culture that held women in high esteem. The fall in the position of women occurred much later; it was written in the first ever legal document about 1700 years ago: Manusmriti. Manusmriti was a good guide to living.

But it also resulted in the over valuation of boys over girls, grooms over brides, and thus the entrenchment of a deeply patriarchal culture associated with gender inequality, power imbalances and culturally distorted practices such as sex selective abortions, and violence related to insufficient dowry. Even dowry murders evolved.

Sadly the impact of colonisation was worse for women. The British colonisers saw themselves as the liberators of women but their government enhanced the value of men.

Was there anything unexpected you gained from writing this book?

I discovered a memory from my childhood. I was five years old and the father of my girlfriend would sit us in his lap. It wasn’t until I started writing that I remembered feeling uncomfortable; I felt something in him touching my leg. It happened just the once.

I remembered running back home, and never going back there. I remembered that I did not feel damaged or vulnerable. But I never told anyone about it. It was a difficult memory but it helped to write about it. Breaking that silence felt liberating.

What are the underlying assumptions that make dowries a possible way that men get away with abuse?

MDO: Dowry abuse is possible because of the cultural assumption that a girl is only ever a guest in her father’s home. That her real home is that of her husband. That boys get to live with their parents, take care of them in old age, get to protect the family name, wealth and eventually inherit their parents’ wealth. So automatically boys are more valuable. The daughter receives a small ante mortem inheritance as dowry; dowry was initially a gift for the bride for her to use during tough times.

Colonisation exacerbated the problem. New research shows that colonisation increased the rates of domestic violence in all colonised countries including Australia. The value of men increased with the British government giving men land titles so the government could extract taxes. Men were also able to procure jobs in government.

Those two factors further increased the value of men. So a dowry that was meant to be the bride’s wealth ultimately became a gift for the groom: to help out men financially when there was drought or little money but no let up in government taxes, a kind of thank you for taking on the burden that is the woman.

The practice of dowry in the South Asian context upholds the value of sons over daughters, patriarchal dominance, a sense of entitlement and increased power within men over women.

With rising wealth following independence, the practice became more toxic and dowry became gifts for the whole extended family. People sort of normalise the bad behaviour as “culture”. It makes it very easy to have a blind spot to the abuse of the practice.

Most families and grooms do not abuse their position of power, but some do. In a national survey conducted last year, we found that 32 per cent of mostly South Asian respondents had either experienced dowry abuse or knew someone who had.

How do you foresee changes, when often in Indian culture, daughters are valued less than sons?

There are many actions that can be taken. In our previous community theatre interactive project, the community members told us that the compulsion to marry off daughters as soon as possible needs to change.

Daughters should not be seen as someone else’s wealth. They can earn and support their parents just like sons. I personally know many families where this is occurring. The daughters are not married and supportive parents. But the societal pressures make them feel self-stigmatised. That needs to change with community education

Community needs education around the value of women and daughters having more voice in the family and decision making power; it will make the family happier and stronger. Seeing women in leadership roles in the community and being respected for their contributions is must.

In your opinion, why has the conversation around domestic violence in Australia lacked so much nuanced understanding of violence that considers culture and ethnicity?

The feminist movement in Australia is largely white in its sensibility. Very few of the women leaders with a voice in the media are women of colour. So it is very rare that these women get to make high-level input.

Australia is a wonderful, multicultural country with half its population having multicultural roots. This is slowly being reflected in our parliament. But that diversity must be reflected at every level and every section of society to effect change.

At the end of your book, you write that you hope for an India that is “free from misogyny, free from women’s inequality, free from ridiculing women.” How can India do this?

I think that in India we are lucky to have inherited that early golden period where women were held in high regard, where women were great debaters, welcomed in kings’ courts and allowed to choose their paths in life.

That is why we probably ended up having goddesses: there was a respect factor. It is possible to get back there but we need to use modern thinking, knowledge and mindset to do this.

In the final chapter I reimagine the verses in Manusmriti that wrote the downfall of women. I hope my modern version of Manusmriti will inspire the modern minds of today and tomorrow.

What do you think the Australian government, or any large welfare body, should be doing to help eradicate these issues?

All governments State or Federal need to include women of colour in decision making process at every level, not just token numbers. Their achievements should be celebrated publicly and their opinions demonstrably respected, just like those of their white counterparts. This I believe will impact public opinion.